For workers raising the Western Hemisphere's soon-to-be tallest skyscraper, “fast food” has an extra dollop of meaning.

With hundreds of eateries in Lower Manhattan, crews erecting the frame of the $3.2-billion One World Trade Center—on schedule to stand 1,776 ft when substantially complete in fall 2013—have only two options when the lunch bell rings: They can frequent a Subway sandwich shop on high or “brown bag” it. However, they can't leave the premises.

The 36 shipping containers that house the shop are dubbed “the hotel” because they also contain lockers and restrooms. The hotel scheme not only minimizes vertical commute times, it prevents hoist congestion.

“The goal is to make the whole tower job move up as if workers are on the ground,” not 900 or 1,200 ft in the air, says Mel Ruffini, project executive for the local Tishman Construction Corp., a unit of AECOM Technology. The construction manager is under contract with the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey to build 1 WTC's $2.1-billion core and shell.

The hotel is novel in its own right, but it serves more than one purpose.

As part of its $256-million contract, local steel contractor DCM USA Erectors Inc. also designed the hotel to stabilize the tower's steel perimeter-tube moment-resisting frame. Under Tishman's “steel first” scheme, the hotel minimizes the needed erection-steel until the structural concrete core, 10 floors behind the steel, catches up.

There's more. Each half of the three-level hotel sits in the core void like two square donuts, each with a tower-crane mast that rises through the donut's center. The location puts a protective roof over Collavino Construction Co.'s concrete crews, who work below the ironworkers.

The roof is also a shield that allows the slower concrete operation to continue in the rain, allowing the concrete to keep pace with the steel. And hatches in the hotel floors let crews install risers on weekends, when the steel and concrete operations are idle.

The hotel is but one prop in a meticulously staged play to meet a demanding schedule for the 3.5-million-sq-ft 1 WTC, originally named the Freedom Tower. Having two tower- crane hooks for two steel operations is another prop that lets DCM jump each crane separately, followed by each hotel half. And that avoids a shutdown of steel erection. “It's like a vertical freight train,” says Ruffini.

A sky-lobby hoist system is another part of Tishman's efficiency plan. To avoid disruptive exterior-hoist shutdowns when winds exceed 30 mph, Atlantic Scaffolding, LaPorte, Texas, is providing hoists inside the building. The hoist scheme had to be planned with the structural engineer because creating a 70-story shaft to floor 100 required leaving out permanent floor beams temporarily and adding temporary beams.

Staying Out of Each Other's Hair

Tishman also developed a tactic to keep the core and curtain-wall operations out of each other's hair. A “slider” crane, which cantilevers off the tower's sloping-in northwest corner, is used exclusively for concrete rebar and lumber. The slider and its mast travel up just above the curtain wall.

These strategies facilitate the erection of two floors every two weeks. The pace is needed to keep the steel frame, currently at 960 ft, on course for topping out in March at 1,386 ft.

Tishman, which reports no deaths or major injuries to date, is obsessed with worker safety. To protect crews, expected to peak at 1,500 this year, Tishman devised another first for a steel frame in New York City: A two- story, lightweight-steel traveling system, called a “cocoon,” wraps the upper limits of the frame in heavy netting and drapes nets down 16 to 20 floors. The cocoon, lifted by crane as the steel grows, contains work platforms that hang off the steel. Ironworkers no longer have to balance on beams.

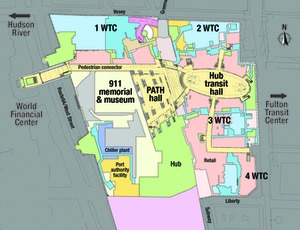

The skyscraper sits in the northwest corner of one of the world's busiest and most congested construction sites: the 16-acre WTC replacement for the 10-million-sq-ft office complex destroyed by terrorists on Sept. 11, 2001. The port authority's PATH rail tunnel crosses under the site. Construction gates have to be shared with seven major projects under way, complicating deliveries. Security is tight. Deliveries are screened.

Before construction began in 2006, Tishman spent months plotting operations, schedules and logistics to determine how to deliver a 1,368-ft office tower, topped by a 441-ft spire, on time, on budget and safely. “We micromanage to the max,” says Tishman's Ruffini. Any delay has a cascading effect on the rest of the operations coming up behind it, he adds.

If a Middle East prince has his way, Saudi Arabia will someday be home to the world's tallest building. Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz recently unveiled a scheme for a 5.3-sq-kilometer city north of Jeddah that would include a mixed-use supertower designed to reach more 1 km above the desert floor.

If a Middle East prince has his way, Saudi Arabia will someday be home to the world's tallest building. Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz recently unveiled a scheme for a 5.3-sq-kilometer city north of Jeddah that would include a mixed-use supertower designed to reach more 1 km above the desert floor.